Safety

Over the years my thoughts on safety for dinghy cruising have evolved a bit. Safety is a personal responsibility. it is up to you to decide what is safe for you. The following represents my current thinking on safety but, I repeat, it is up to you to decide what is safe for you.

The safety issues associated with dinghy cruising are a bit different from those associated with dinghy racing and with yacht cruising. In organised dinghy racing you will be operating close to shore facilities and have a rescue boat on hand. This contrasts with dinghy cruising where you may be operating in a remote location without a rescue boat on hand and emergency rescue services may be hours away. In this regard we are similar to a cruising yacht. However we have the additional hazard in that we can capsize (but hopefully recover). We are also very much exposed to the elements, and the small size of our boats makes us more vulnerable to the sea state.

These factors mean that safety requirements that are usually accepted for dinghy racing and/or for yacht cruising are not always appropriate for dinghy cruising. I find that quite a few compromises need to be made, some of which are not ideal. There are things that keep you safe while your boat is upright but can hinder you if you are capsized.

Be Legal

Needles to say you must satisfy the legal requirements for your local sailing area. That is, you should carry the required life jackets, radio, flares, EPIRB, anchor etc. However, what makes you legal may not be enough to make you safe.

Lifeline

I mostly sail singlehanded and consider the lifeline to be my most important piece of safety equipment. If I could carry only one item of safety equipment and nothing else this would be it. If all else fails as long as I remain attached to my boat I have a chance of survival. If I become separated from my boat when offshore I would reasonably expect to die. A capsized boat can drift much faster than you can swim when you are wearing your sailing gear.

The lifelines that you buy are typically fairly short. This is deliberate. In the intended use case on a yacht it is important that you do not end up falling so far that you drag in the water. If this happens you can drown. However, on a cruising dinghy I believe the lifeline should be reasonably long. I extend mine with a length of rope. You need enough length to be able to capsize and move around the boat in the water without the lifeline stopping you or pinning you in a bad position. Once the situation has stabilised it may then be appropriate for you to unhook in order to right the boat.

As long as your boat is not large there is no danger of the boat continuing to sail and dragging you if you fall off. I have tested this on my Navigator, the drag of my body in the water immediately stops the boat. However, if you test this on your boat make sure you have a second person on board for safety. When you use a lifeline you should also carry a knife for emergency release.

Even if you are sailing two up consider wearing life lines. As a teenager I 'lost' my skipper off a surf cat on a very windy day when his leaning strap broke. By the time I eventually turned the boat around I had considerable difficulty finding him again, his head was very hard to see in amongst the waves. A sobering lesson for both of us. This was just in the river with the wind chop.

Life jackets and buoyancy vests:

Be wary of inflatable jackets

This is an area where the thinking of myself and some of my sailing colleagues has evolved over the last few years. I used to simply wear an inflatable life jacket. They were convenient, unobtrusive and made you legal. I now think they are potentially hazardous for dinghy cruising.

Indeed, it is worth noting that in the Australian Sailing Special Regulations Part 2 for Off the Beach Boats Regulation 5.01.3 states that "Inflatable lifejackets shall NOT be used."

It was an incident involving a sailing colleague in a capsize that made us reassess the appropriateness of inflatable jackets. The boat had capsized and turned turtle. He was about one metre away from the stern of the boat when his inflatable jacket was inadvertently inflated. He never reached his boat!

Once inflated his life jacket rendered him helpless. All he could do was float, there was no way he could swim effectively. Despite extreme efforts on his part he was unable to keep up with his drifting boat. Sailing nearby with a friend we picked him up. He was in a state of total exhaustion from his attempt to reach his boat.

An inflatable life jacket is appropriate where, in an emergency, all that is required is that you float. For example, if you fall off a yacht or your boat sinks. However, if you need the ability to self rescue, for example, right a boat from a capsize then an inflatable life jacket may be a hazard to you. While it is uninflated the jacket will weigh you down by somewhere between 0.6kg and 0.8kg hindering your ability to float while you try to right the boat. If you inflate your jacket your ability to swim and to right the boat may be made impossible.

A buoyancy vest is the ideal thing to be wearing when trying to recover from a capsize. You have some supporting buoyancy while not being greatly hindered in your ability to swim, right the boat, and climb aboard. However, wearing just a buoyancy vest may not be legal offshore and it does not provide the full level of floatation you want should the worst occur.

The solution I have adopted is to wear both a buoyancy vest and a life jacket. In addition to my buoyancy vest I wear a Marlin L100 Adult Waistbelt. These are mainly marketed at standup paddle boarders, and wind and kite surfers. These can be worn around your waist just below a buoyancy vest. The idea is that if you end up in the water you initially rely on the buoyancy vest and only deploy the waistbelt if the situation demands it.

My buoyancy vest provides 50N of floatation and the Waistbelt provides an additional 100N giving a total of 150N. This matches the floatation of a typical inflatable life jacket. Here is the operation sequence of me trying it out by manually inflating it with the inflation tube, fitting it over my buoyancy vest, and jumping in the water. I was worried that some issues might arise in wearing both a buoyancy vest and a jacket but so far I have not found any problems. No doubt the addition of a crotch strap would probably be useful.

Some 'assembly' is required, you need to pull the jacket over your head. However you do have the benefit of already wearing a buoyancy vest to support you while you do this.

A constraint of any waistbelt design is that you only have a strap around your waist. There is no additional strap that goes up your back to the rear of the collar around your neck. Initially I was concerned that that the collar could potentially slide off back over your head. However, in my tests I found that I had to bend my head over a fair way in order to get the collar over my head and once I straightened up just a little it was clear that there was no way the collar could slide off. In fact this jacket design is widely used, most aircraft life jackets only have a strap around the waist.

To my mind this arrangement seems perfect, but not quite. If you want to wear a safety harness and lifeline one has a problem with the routing of the lifeline. With a normal inflatable jacket you wear the harness under the jacket and route the lifeline through the middle of the jacket to the harness. With a waistbelt and buoyancy vest this is a bit problematic.

Firstly, with your harness under your buoyancy vest you will find that the harness line has to exit from under the vest. If the harness line is tensioned it will tend to lift the vest and push it up towards your chin. Secondly, if you deploy the waistbelt with the lifeline connected the jacket will end up over the lifeline which now has to exit out sideways. Should the lifeline get loaded it will lift the jacket and possibly damage it. To resolve this you could unclip, and reclip your lifeline through the jacket but this is obviously not ideal. It is possible to re-route the lifeline through the waistbelt jacket when you pack it into its pouch but this means that if the lifeline is loaded it will open up the waistbelt pouch which may not be what you want.

I have decided to accept these problems. In normal sailing my waistbelt will not be deployed, thus if I fall off my boat there will just be the interaction of the lifeline and the buoyancy vest to deal with. This I am not greatly worried about as I believe the period when the lifeline is under significant tension will be very short. If I subsequently need to deploy my waistbelt then I accept that I will have to unclip and re-route the lifeline. Not ideal, but this is the compromise that I have chosen to accept.

Carry key safety gear on your body

The two situations in which you are most likely to require emergency rescue is if your boat has capsized, turtled and you cannot right it, or if you have become separated from your boat. In these situations all the safety gear on your boat is for naught. You cannot access it.

The only solution is to carry some key items on your body. If offshore I carry a PLB, Spot Tracker, hand held radio, small signaling torch, and a knife in my buoyancy vest pockets. With this you are equipped to alert rescuers and guide them to you. Unfortunately life jackets do not tend to have pockets in which you can carry this sort of gear. However kayaking vests are available with plenty of pocket space. They are typically much better for our kind of sailing than standard sailing buoyancy vests. My kayaking vest can also hold a drinking bladder in the back. This is convenient for everyday use and potentially an aid to survival.

Unfortunately carrying all these items adds a surprising amount of weight to your buoyancy vest. Not what you want if you have to climb back into your boat. You are also quite likely to damage these items in the process of climbing back in over a gunwale.

Alan Stewart of B&B Yacht Design has a very good video on how he sets up a PFD for small boat sailing. This is well worth a watch. He carries a very much more comprehensive set of items than I do.

Mainsheet cleat: The most dangerous thing on your boat?

I wonder whether the mainsheet cleat is the most dangerous thing on your boat. So many capsizes seem to be caused by them. I do not have a cleat, I just use a good rachet block instead. This is relatively easy for me as I have a balanced lug rig where the sheet loads are low. If you have some other kind of rig try a rachet block instead of a cleat and possibly add an extra purchase to your system to reduce the sheet load.

Life without a cleat is made easier if you know the right way of using your tiller extension in conjunction with the mainsheet.

Clothing

This is an area where I feel there is no ideal solution for cold weather sailing. We have to make a compromise between comfort and safety.

If it is cold a wetsuit is probably the safest thing to wear. It keeps you warm wet or dry, provides some floatation in the water, does not absorb water and stays light on your body when you want to climb back into your boat.

But most of us don't want to wear wetsuits all day. Instead we use standard sailing wet weather gear. This gear is great when the boat is upright but if you capsize this gear hinders your ability to swim and soaks up a lot of water making it hard for you to climb back in. If you soak your gear in water, then lift it out and immediately weigh it you will find it weighs something like 5 to 7 kg.

Don't do up the ankle cuffs on your wet weather sailing trousers! If you do so you will find your legs encased in several kilograms of water when you try to climb back into your boat after a capsize. You want water to be able to drain out of your trouser legs.

On thinking about it, the times when I have had difficulties have mainly been due to getting very cold from setting off on the day with not enough wet weather gear on. Once the wind gets up it is difficult to change what you have on, especially single handed. Clothing is a really important part of being safe.

Keep the boat dry

I have a venturi/Anderson bailer fitted beside the rear of the centre case. When things are rough and you are getting spray over the deck a significant amount of water can accumulate in the bottom quite quickly. The free surface effect will then degrade your stability. In these conditions the last thing you want to be doing is having your head down in the bilge bailing things out, or using one hand to operate a bilge pump. I simply push my venturi down and it happily sucks the water out leaving me with both hands free to manage the boat. (Just make sure it seals properly when it is up so that you do not leak when at anchor.) It would have been better if I had fitted two venturi, one on each side against the side tanks. This would allow me to keep the boat dryer when heeled on either tack.

Mast floatation and drainage: Allow it to drain out the top

Ideally your mast is perfectly sealed. However, achieving a perfect seal is hard. With a turtled boat 5m of water pressure acting at the tip of your mast can result in a surprising amount of water coming in through rivet holes etc.

If your mast is not sealed you need drainage holes at the bottom and at the top. When you bring the boat up from a capsize you want water to drain rapidly out of the top of the mast as it goes from tip down to horizontal. At this point the mast should have little water in it allowing you to bring the boat upright more readily.

To provide some floatation in my mast, and to reduce the volume of water it can hold, I fill my mast with foam swimming noodles. I had to trim them down a bit with a hot wire to fit within my mast.

Climbing back into your boat

In my view climbing back into your boat is a problem for which we have not really come up with a good answer.

You need to be able to climb in over the side of the boat. Climbing a ladder on the transom is not an option in any kind of breeze. The boat will pivot away from you, point downwind, and with all sails filling sail away from you.

I use two capsize boarding lines under my gunwales. These are similar to the re-entry slings devised by Howard Rice for his SCAMP. On Whimbrel I use 12mm ropes that run just under the gunwale from the stern to the main bulkhead. Pulling at the centre of the ropes they stretch out to about 700mm away from the gunwale. I replaced the rope cores with shock cord so that they are held up against the underside of the gunwales when not in use. The remaining rope sheath is strong enough for what is needed. The lines are very handy.

- I can use the righting line as a step for my feet when climbing back in after a capsize, or a swim.

- They give me something to hang onto when I am in the water beside the boat.

|

|

In practice using the lines is not as easy as it looks in the photos above but they help considerably. An additional thing that helps a lot is a line that you can use to pull yourself in. I have lines attached at the front of my centrecase that lead out to the gunwale. They are held out at the gunwale by shock cord.

Remote steering

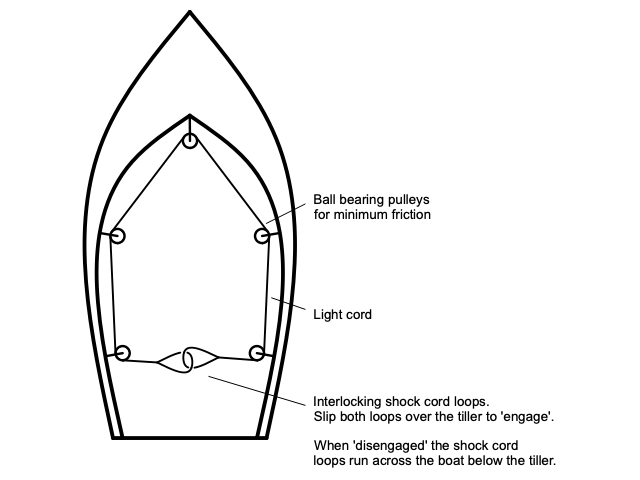

One thing that makes the boat easier to sail, and hence safer, is a line running around the inside of the cockpit with shock cord loops that can the slipped over the tiller. With this you can steer the boat from anywhere in the cockpit. I find this very useful (invaluable!) when you want to go forward to reef your sail or to get something from a hatch. In light weather you can position yourself anywhere you like to get into the shade of the sails and out of the sun.

When steering with the lines I use the nemonic 'sliding the line clockwise around the cockpit steers the boat clockwise' and vice-versa.

Safety through sailing ability and risk assessment

All the discussion above has concentrated on safety equipment. However, what is probably far, far more important is your competence in how you sail the boat and your competence in assessing risk.

If you have a solid boat, such as one of John Welsford's designs, and have it set up so that all the systems work well, reefing works well, and the sails set up so that it can go upwind well, then the boat will be quite safe. What remains is that you have to ensure you operate the boat safely. You have to be totally competent in handling the boat in all conditions, and competent in assessing the risks you may be facing in any situation.

You need to ensure you can handle a dinghy in strong winds and large seas. You must be able to stay warm, dry, and fully functional in horrible conditions. Go out and practice on days you would not normally go out to sail. Gradually working up to nastier and nastier days. Each time you will find things that will go wrong. Learn from them and fix them. Eventually there will come a point where you will know for yourself when you are ready for an unsupported sailing expedition. If you have a background in sailing racing dinghies you are well placed. You will have gone out in all conditions, learnt to tack and gybe when you have to (not just when you feel like it), and you will have developed your skills in handling an overpowered boat in strong winds at speed.

The other major part of being safe is having a good understanding of what can go wrong in various situations. You can only get this understanding by experience and talking to people with experience. If you have an understanding of what might go wrong then you are in a position to make sensible risk assessments. If (somehow) you can anticipate all the things that could go wrong, and have a plan for dealing with each of them, then you will succeed. It is the things you do not anticipate that cause you grief.

So many tragedies, sailing or otherwise, are caused by people putting themselves in situations where they have not understood what could go wrong. Without this understanding they could not make any sensible risk assessment and hence not understood the dangers they were putting themselves in.